They say that the Cerro del Tío Pío is the best viewpoint in Madrid. They say that the tits of Vallecas are the Tibidabo of the capital. From its hills, seven mounds that rise in the district of Puente de Vallecas, the sunset is a free five-star show. Even today, some children throw themselves from the top of the park with flattened cardboard boxes and slide down the grass as if it were snow. This image has been repeated for almost 40 years at this very spot. Back then, in the 1980s, the park was very different, dirt and rubble. Rubble of shacks that had given shelter to thousands of people. Rubble that was buried under the tits of Vallecas. Seven hills, seven sites of the most recent past.

Views of Madrid from the Cerro del Tío Pío hill. | Shutterstock

Nestled in the neighborhood of Numancia, the history of the Cerro del Tío Pío has its origins many years ago, specifically in 1918. At that time, only a few houses flourished in the area. One of them belonged to Pío Felipe Fernández, who was ‘a construction worker, a farm worker or whatever came out’. At least, that is what Carmen Rodríguez Felipe, one of the old neighbours, said in the documentary Fontarrón: 25 years of a neighborhood. This man bought the land and rented it to new tenants. This, by the way, is the reason for the name of the park.

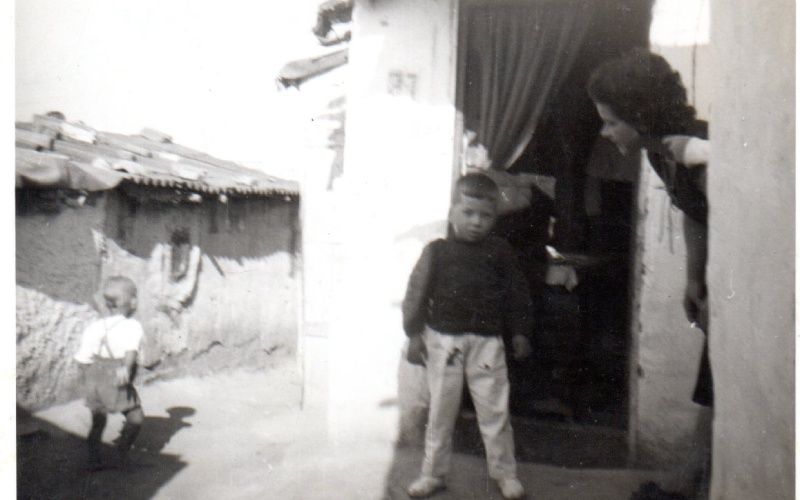

Although it was not possible to build, the people who rented the land for ridiculous prices took advantage of the night to build their houses. Sometimes, the Civil Guard would tear them down again, until they ended up turning a blind eye. These were the beginnings of what would later become one of the largest shantytowns in Europe. In 1925, when Vallecas was still a town, the town council officially recognized the settlement and baptized it as the Pío neighborhood. A census of 90 people in 22 dwellings was taken.

At that time most of the neighbours shared two characteristics. The first was that they were immigrants from the interior. Most often they came from Murcia, Guadalajara, Cuenca or Madrid with the intention of improving their living conditions. The second commonality shared by these individuals was their situation: workers whose resources were insufficient to live elsewhere.

The Pío neighbourhood had, of course, neithher water nor electricity, nor transportation. The Puente de Vallecas subway, the nearest station, was 1.5 kilometers away. The workers, in many cases, chose to walk to their respective jobs. The soil, which was clayey, was always muddy and allowed some of the neighbors to build caves in the purest Andalusian style instead of houses.

Over time, the number of residents increased, although the most significant increase came after the Civil War. Andalusians, people from Extremadura and La Mancha were the most common new tenants. Thus, in 1950, the year Vallecas was annexed to Madrid, the official number of residents reached 544 people. A decade later, in 1960, the population was no less than 4,148 individuals. This situation led the poet Pedro Garfias to describe the Cerro del Tío Pío as ‘the symbol of all the suburbs of Spain, of all the suburbs of the world’.

Cerro del Tío Pío Park nowadays. | Shutterstock

According to the documentary Fontarrón: 25 years of a neighborhood ‘by 1965 these nuclei were almost completely formed’. ‘The 1963 general urban development plan,’ it continues, ‘gave them legitimacy.’ However, in those same years Madrid did not stop growing and, with the construction of dormitory cities, Vallecas was closer to the center than other metropolitan areas and its land was revalued. At that time the so-called partial plans, ’16 in all of Vallecas’, arose.

Fabián Fernández de Alarcón, another of the neighbours who lived in the Pío neighbourhood, explains in the same documentary that ‘they wanted to remove all the low houses and make a partial plan in which the land would be recovered for large housing developments‘. But the residents of this and other shantytowns in the district joined forces to oppose the plans. With the cry ‘Vallecas is ours’ the tenants rose up in struggle.

In 1976, a demonstration brought together 50,000 people from Vallecas. Two years later, in April 1978, they created Orevasa, a public company that sought, among other things, to streamline the bureaucratic procedures for evictions. The singer-songwriter Luis Pastor, who grew up in the area, sang “come on, don’t think twice, join your neighbors, the partial plan will catch you”. Finally, the people of Valle del Cauca managed to get 12,000 homes for the families in this and other shantytowns, and the slums began to be cleared. Many of the residents ended up in the Fontarrón neighbourhood.

A boy and a woman in the Pío neighbourhood in 1959. | History Museum of Madrid/Digital Library Memoria de Madrid under license CC BY-NC 2.5 ES.

Meanwhile, on the Cerro del Tío Pío the destruction of the shantytowns had given way to a sea of ruins from which, on the other hand, privileged views of Madrid could be enjoyed. The architect Manuel Paredes was the one who initiated, in 1985, the construction of the park. Paredes then decided to cover the rubble instead of moving it to the landfill. Thus were born the seven tits of Madrid, seven hills that were erected on the remains of the working class of the 20th century. Seven hills that are now green and for which their neighbours, 40 years later, continue to feel great affection.